In an increasingly-complicated world, we’re constantly using shortcuts to make sense of things. We don’t have time to process everything coming our way, so we often grab one or two salient data points — either the things we notice first, or the ones that feel more important to us — and do math.

This makes sense. It would be impossible for us to sift through all of it, in every situation.

Just ordering coffee, if you really wanted to consider all the variables, would take a month — what roasts do they have, what’s the source of the beans, how they were dried, the ownership of the farm, the ownership of the shop, which of the 20 types of milk you want, where each of those is sourced, and so on.

Instead, we choose from a few variables we prioritize. Maybe price and size. Or if ethics are important to us, we might decide by looking for a “Fair Trade” stamp on something locally roasted.

In that case, we’re trusting that the sticker means we’re making the right choice, instead of doing all the investigation ourselves. It’s a shortcut. If it adds up, we say “I’ll have that.”

No problem if we’re ordering coffee. The heuristics of “price + size = decision” or “Fair Trade sticker + locally roasted = Yes” aren’t likely to cause too much pain in your life.

But when we’re making other decisions, basing them solely off of one or two bits of information — particularly if they just happen to be the first bits we learn — might get us into hot water.

Here’s one such heuristic: “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” and its inverse, “the friend of my enemy is my enemy.”

And following is a common way we’re applying it, and three ways we’re getting burned.

“If they hate you, you’re doing something right.”

This sentiment is a variation of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” that I’ve heard so many times I’ve lost count. Whenever someone finds out my work is getting protested, or I’m receiving hate mail, or even death threats (all of which have become like water for me), it’s likely that this sentence isn’t far behind.

What they’re saying is that as long as the people protesting my work are the right people (i.e., the “wrong” people, or people the speaker things are wrong), the very act of them protesting my work means that it’s good work. It’s helpful. It’s to be celebrated.

Most of the time, the people saying this don’t even know my work. They haven’t read the essay or book in question, or seen the show or documentary themselves. And they won’t. They don’t need that data point.

All they need to know is that a group that’s their “enemy” has labeled my work as “enemy.” Therefore, my work is “right.” Or it’s good. Or it’s worthwhile, helpful, just, positive in the world. I’m “fighting the good fight.”

I believe all those things are true about it, but I don’t believe it because a certain Fox New correspondent attacked my work, or some conservative Christian Right organization boycotted me. Those aren’t data points I consider (at least I didn’t consider them at first — I’ll get to this in a bit).

This phenomenon carries further than the sentiment being expressed. It’s not limited to people saying, “If they hate you you’re doing something right.” People have effectively leveraged this into crowdfunding campaigns, fundraising in general, fame and platform-building, and have created entire careers, seemingly, just by being hated by the right people.

And I see “enemy of your enemy” everywhere I go in Social Justice Land.

On social media, people wear attacks from the other side as badges of pride. As proof that they deserve a seat at the table. That you should listen to them, and that they’re “one of us.”

I just opened Facebook, and the first post I saw, from a social-justice-supporting friend of mine, was a meme from the page “Hate Liberals? Bite me.” After that, I opened Twitter and clicked through to the bios of three of the most recent tweets that people retweeted into my Twitter feed. One person’s included the phrase “most hated writer at…", one included a slur in quotes they (I assume) get called by their homophobic detractors, and one simply said, “Hated by Fox News and the right wing.”

Further, it’s important to note that this heuristic is deployed across parties and movements and ideologies. It’s not just a thing social justice people (or the dogma within the movement), or progressives, or liberals do.

It’s actually something many conservatives, particularly the more modern, young, or tech-savvy ones, have perfected. There’s a booming industry of “owning the libs” — in apparel and products and entertainment and “news” — and business is good. And this isn’t even a secret.

Of his ability to effectively exploit his followers’ hatred of “social justice warriors,” Jordan Peterson said:

“I’ve figured out how to monetize social justice warriors. I’m driving the social justice activists in Canada mad because, if they let me speak, then I get to speak. And then more people support me on Patreon. It’s like, “god damn capitalist, he’s making more money off of this ideological warfare. Let’s go protest him.” So they protest me. And that goes up on YouTube. And my Patreon account goes way up.”

Publicly. He said this publicly. In an interview his followers (i.e., Patreon funders) were meant to be watching, not caught on a hot mic.

You’d think this would irk his fanbase, to know he’s knowingly reduced them to an algorithm of “enemy of enemy is friend I give money to,” but instead this was cause for celebration.

The First Problem: Non-starter

One of the problems that comes with this line of thinking feels so obvious to me that it’s unnecessary to explain, but it’s not obvious enough to prevent people saying it (hundreds of times to me over the years, and I’m sure billions of times in general).

So here’s the obvious: a lot of stuff our “enemies” hate isn’t that great. That is, “just because they hate you,” doesn’t mean you’re doing something right. It just means they hate you.

If one of our “enemies” identifies a social justice person, idea, strategy, theory, etc. as “an enemy,” that doesn’t mean they’ve found something we should support, or that what they’ve identified “is right.”

It’s possible they picked an idea we otherwise wouldn’t have supported, or gotten behind, or rallied around — or even an idea that we, ourselves, thought was wrong. I’ll go even further.

It’s not only possible, but likely.

Because there are plenty of bad ideas, unhelpful actions, inneffective strategies, and problematic theories that get shared in the name of social justice. Maybe even most of the ideas we share won’t work — this isn’t a slam on social justice people; it’s just the nature of the work we’re doing itself. We’re trying to create something that hasn’t happened yet. It’s the problem of progressivism. We’re likely to have more ideas fail than succeed. We’ll experiment, and prevail through trial, error, tweaking, then trying again.

The worst ideas, the ones that not even most of us would agree are good, are the easiest targets. So it makes sense that an “enemy” would take a shot at them. Which brings me to the second roadblock. Actually, roadblock isn’t right.

The Second Problem: Tainted Fuel

The second problem with this line of thinking makes a roadblock seem ideal by comparison: It’s more like we’re giving our “enemies” control of the GPS. We’re handing them our phone, saying, “Where to?”, letting them type in a destination, then driving there at breakneck speed.

If we all pile in to support something that our enemies hate, we’re giving them power over what we choose to support. This heuristic doesn’t just say, “If my enemy hates it, I’ll support it,” it says, “If I hate this, my enemies will be inclined to support it,” and “If I like this, my enemies will be inclined to hate it.”

This can be easily manipulated by the people we call our enemies, to say the least. And that might be worth us diving into, but even if they don’t manipulate it, it’s hard for us not to be motivated by this ourselves.

I mentioned earlier that at first, whenever I was creating a new thing, I never considered whether or not my “enemies” would hate it. And that’s true. The idea had never crossed my mind.

Instead, and this feels so naïve, I merely focused 100% of my attention on trying to create things for people to use, appreciate, or love. Imagine that! I was making things for “my people.” For the people who shared my goals to advance them. Oh, what a time to be alive.

But now, after hearing hundreds of people say “If they hate you, you’re doing something right,” and feeling the recognition that is accompanied that when it happens, it’s become impossible not to consider than when I’m creating something. I’m still not saying I factor it in, but it’s absolutely on my mind every time I’m working on a new project (more on that down below).

Because here’s the sad truth: creating things your enemies hate is way easier than creating things your allies love.

And intense negative emotion spreads faster via social networks than positive emotion (not just Facebook, but also the good ol’ fashioned grapevine). How often do you hear positive gossip? When was the last time someone was just absolutely chomping at the bit to tell you about that really nice thing that happened at work?

You might be noticing that we’ve stumbled upon a sort of formula, much like Jordan Peterson’s above: if we want to create something that spreads like wild fire, the easiest thing to create will be something my enemies hate.

Here’s where I want to pump the breaks: I’ve never created something based on this formula. And I’m not even accusing Peterson, or anyone, of doing so. I’ll let them speak for themselves.

What I’m saying is it’s tempting.

I’ve created hundreds of websites for social justice over the years. And some of them have taken off, and lots haven’t. It’s been arduous, required patience, and is sometimes mystifying why something you’re sure your people will love, that some of them tell you they do love, never seems to make it around the horn.

Meanwhile, I’ve seen tons of people follow the formula above and create overnight successes that are built on nothing but reactionary hatred and superficial tribalism, nothing more than being the enemy of your “enemy.”

And you don’t even have to do it on purpose.

A lot of the most trendy “enemy of my enemy” stuff isn’t planned — and likely couldn’t have been. Someone makes a thing. Shares it into the world. Then it just happens. Like a tsunami without warning. After that, it’s up to the creator to ride the wave. Surf or sit out. That’s the only say they have in the matter.

And a lot of people choose to ride that wave for years — fueled and funded by the the friendship of enemy’s enemies for month after month — even if they never end up being able to create another wave. Maybe because they know they won’t be able to create another one.

But it would be understandable if someone thought that was their best bet.

If someone had seen others rocketed into the stratosphere by the hatred of their “enemies,” and the support of their enemy’s enemies, it makes sense that they might think that was their most likely path to success.

This is the essence of this problem with the “enemy of my enemy is my friend” heuristic: suddenly, your “enemy’s” decision about who is their enemy, is dictating your friendships.

The things you like, support, or want to create are susceptible to being dictated by what your “enemy” hates. Or, if you’re the creator yourself, you’re incentivized to create things that your “enemy” will hate, driven to identify the types of things they will identify as their enemy, and make those things — whether or not they’re things that align with your goals, or what you want to see happen in the world.

And as soon as that happens, you’re no longer as worried about where you’re going, as you are about going somewhere.

Even if that somewhere you’re going happens to be a path charted by your “enemies.” And in that moment you realize they weren’t you enemies at all, because if you’re basing your actions off of them, your fuel is their negative energy (the more they hate you, the further you go), and your flight path is dictated by their reactions to your work, “enemy” is the wrong word to describe them. They’re your true allies – your copilots – and the people you were calling your “allies” are just customers buying tickets to ride the plane.

The Third Problem: Backfire

Once you go down the course of starting to factor in “the enemy of the enemy is my friend” as you’re creating things, or making decisions, or forming opinions, we have the third problem: the reverse of “If they hate you, you’re doing something right,” is also true.

And it might be even more motivating than the original statement itself: If they don’t hate you, you might be doing something wrong.

What does it mean if “they” don’t hate you?

It might mean they don’t care. They haven’t even noticed you. And that’s not good. That means you’re not being enough of an “enemy.” Or you’re just not getting noticed enough.

Or, even scarier, what does it mean if they appreciate your work?

By the above heuristic, “them” (i.e., the “enemy”) appreciating your work should send shivers down your spine. It means you’re not not doing something right, but you might be actively doing something wrong.

And god forbid they see you as “one of the good ones.” One of “the few people in your camp who are making any sense.” That might as well be a death sentence.

Because if they see you as one of the good ones, or as someone who is making sense, and they don’t see you as the enemy, then all of a sudden you’ve become the enemy – or at least indistinguishable from the enemy, which is essentially the same. You’ve become the friend of the enemy, which is our enemy.

So not only are you motivated to create things that your enemies hate, as we covered above, but you’re also motivated not to create things your enemies might like. And any sense that your enemy likes something is an indicator you did something wrong.

The result of this is that “reaching across the aisle,” or “compromise” are out of the question. You’re also discouraged from trying to convert anyone who might be deemed “enemy.” No cavorting with them, or understanding their pain, or building relationships there – it doesn’t matter if your goal is to help them see your side of things, or even just to better understand your opposition. Step foot in their camp, be seen favorably by one of them, and you are one of them.

When that happens, someone in your former camp – in a weird twist of allegiances – is able to benefit from the “enemy of my enemy is my friend” heuristic, only suddenly you’re the enemy. You’ve become the enemy of your friends.

Beyond Enemies

Hopefully it wasn’t too annoying, but I repeatedly used quotes when I referred to “enemies,” above, and I was doing that for two reasons:

- Our framing of people who disagree with us as enemies is a construction of language. It’s not necessarily true that they’re our enemies, nor does it have to be if it currently is. It’s up to us to make that, or unmake it, and we vote for our side every time we speak, and use that framing.

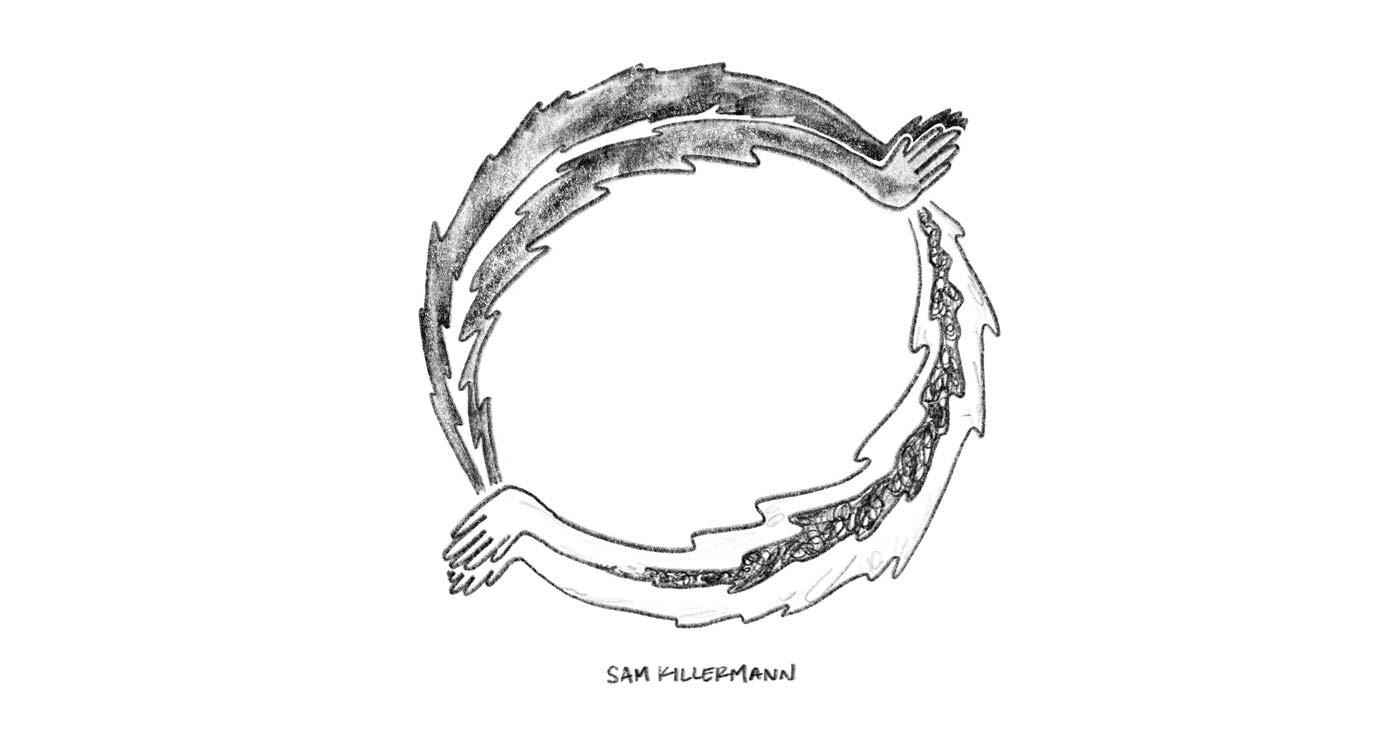

- As you likely realized, the enemy-enemy relationships established by the “enemy of my enemy is my friend” heuristic are actually not typical enemy relationships at all. They’re instead quite symbiotic, relying on the other to survive, where the roles of enemy and friend are fluid, interdependent, and even transferrable.

I would love for us, within the social justice movement, to move beyond the framework of “enemies.” Enemies are a quick way to create friendships and alliances (as we covered in the Appeal of Dogma), but not without costs.

Organizing our efforts within a framework of “Enemies” is likely more harmful than useful, creating as many problems as solutions. If social justice really is equity for all, then there is no room for enemies – unless we’re here to serve our “enemies.”

But I don’t think we even need to move beyond that framework broadly, to see the unique pitfalls to this “enemy of my enemy” heuristic. It’s a non-starter, it’s commandeering our course, and if we let it motivate us it’s likely to backfire.

You might be thinking that I’m arguing here, now, for removing the use of a simplified heuristic altogether. That I’m saying you should fully investigate every position (to it’s absolute source, crunching all the research and data long the way) or person (all of their past actions, beliefs, attitudes, etc.) before aligning yourself with them or not.

That’s not what I’m saying. That idea might be appealing, or feel like a solution, but it’s not. Even if we had the inclination and energy and interest to do so, that wouldn’t work.

Take Thomas Thwaites hilarious attempt to build his own toaster, for an example. The adventure, which ensued over the course of many months and countries visited, had Thomas sourcing raw materials, researching skills for processing them, hitting all types of barriers and overcoming them, all to end up with a misshapen lump of sadness that barely resembled a toaster. And when he plugged it in, “there was 240 volts going through these homemade copper wires, homemade plug. And for about five seconds, the toaster toasted, but then, unfortunately, the element kind of melted itself. But I considered it a partial success, to be honest.”

The lesson here: If you want a toaster, you’re better off taking a shortcut than trying to make your own.

Rely on a the massive, interconnected global network of suppliers, manufacturers, and distributors that you know nothing about, and make your decision based on a couple of data points that you care about (e.g., like price and size).

I’m not saying we should all build our own toasters.

I’m saying the heuristic of “enemy of my enemy” is broken, easily hijacked, and more likely to create a codependent spiral toward doom than it is to give us social justice.

We can’t crunch all the data. We absolutely need simpler heuristics. We just need ones that work. Not because they generate a lot of energy (because we’re clearly doing that, melting ourselves in the process), but because we notice that we’re accomplishing our goals as a result of them. We’re making toast.

And here’s my first suggestion for the replacement:

When we turn it on, we pay attention to what happens. What the outcome is. And if it’s that it melts itself, we don’t count it even a partial success.