Let’s say a friend of yours made a New Year’s resolution to stop being on their phone during dinner. It’s January 4th, you’re sharing a table, and you catch them peeping their insta. You call them on it, they apologize, and put their phone away.

Hypocrisy, meet behavior. Behavior, meet change. Huzzah!

That’s how calling someone out on their hypocrisy works. There are a few important factors here:

- The person you’re calling out has stated (or otherwise believes) that they want to walk a particular (moral) path: “From now on, I’m going to do X.”

- You notice their actions are contrary to that, and actively getting in the way of them living that espoused value, or walking their talk.

- You point out this gap: “You said you were going to do X, but now you’re doing Anti-X.”

- This prompts cognitive dissonance, and they have to pick a path: do as they said they’d do, or give up on that moral stance.

Each one of those four steps is necessary. They work as a chain reaction.

Welcome to Hypocrisy Theatre: Where Social Media is Our Stage and Our Audience is Only People Who Already Agree With Us

For several years now, there’s been a new show in town: Hypocrisy Theatre. And unlike the example above, Hypocrisy Theatre isn’t effective in changing the hypocrite’s behavior. Indeed, they’re not even part of the audience.

Maybe you’ve caught a performance of it?

The cast changes daily, but the show always follows the same script: some random person on social media points out that some other random person they disagree with once said something that flies in the face of a thing they’re saying now.

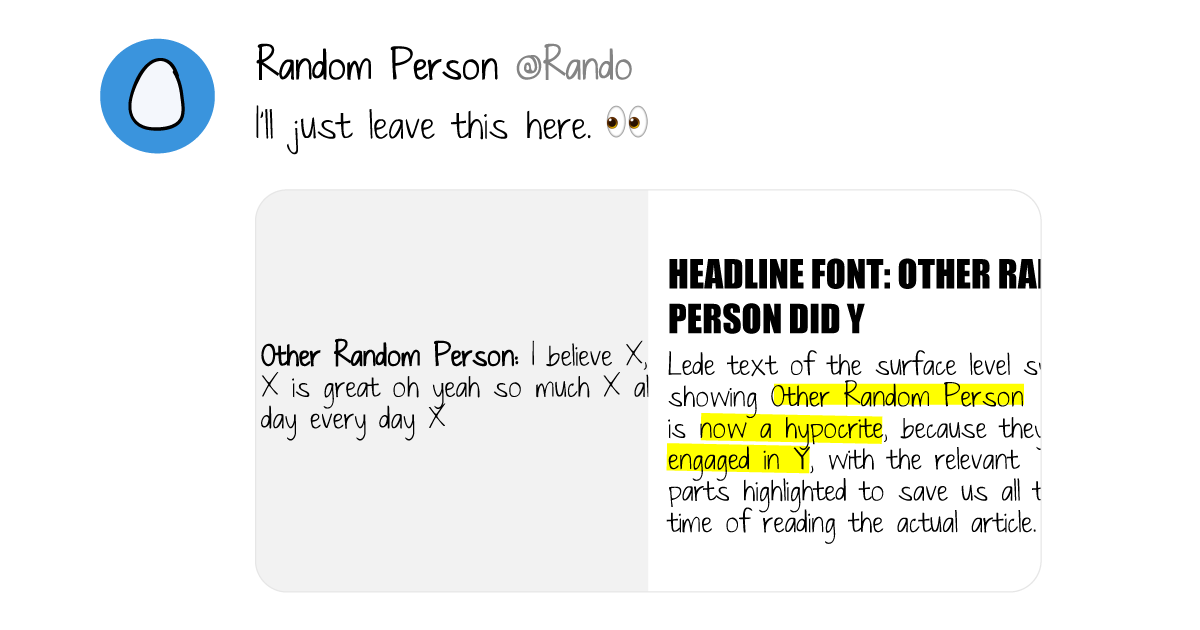

It often looks like this:

(I’m keeping this vague, instead of citing any of the 10 examples I just saw in my Twitter, because I’m doing my best not to publicly drag people here. But you can fill in the blanks. Or just scroll your social feeds — I’m guessing you’ll catch a showing in the wild.)

Hypocrisy, meet behavior. Behavior, meet continuing on the same path unabated. Huz oh no.

That’s now how this is supposed to work.

Why This Doesn’t Work

Hypocrisy Theatre, at face value, is similar to the Phone-at-the-Table Example above, but it never plays out that way.

There are a load of reasons why.

First, I want to point out how these examples are different, then it’ll be more obvious why Hypocrisy Theatre doesn’t work.

In the Phone-at-the-Table Example, you:

- Personally knew the person you were calling out;

- Recognized that their behavior was directly antithetical to their goals.

- Called them out, with a message that was directed at them, and explicitly for their benefit. You wanted to help them line up their values and actions.

- And your message invoked cognitive dissonance: it made them see that they weren’t walking their talk, because they sincerely weren’t.

None of those are necessarily true for Hypocrisy Theatre.

Instead, generally speaking, in Hypocrisy Theatre, you:

- Don’t know the person you’re calling out;

- Recognize that their behavior is directly antithetical to your goals.

- Call them out to your people, with a message that benefits you (by raising your status, or making you A Good One) or your cause. You don’t care if they align their values and actions.

- And your message doesn’t invoke cognitive dissonance in the mind of the hypocrite (if they even received the message), but instead invokes outrage or disgust or galvanizes a “that person sucks” feeling within your circle.

Maybe that lines up for you? Maybe you’ve seen examples of this in your social media feeds? Maybe you’ve participated in it? I can, unfortunately, say “Aye” to all three.

Some of those might be negotiable.

It might work well to call out strangers, or with a paper-thin artifice of it being about “their goals,” or to do so publicly (messaging to your audience primarily, instead of them) — all of those things might work.

It depends on the situation.

But there’s one thing that’s an absolute dealbreaker, and separates Hypocrisy Theatre from the real thing.

The cognitive dissonance comes from someone recognizing their actions aren’t lining up with their values.

Cognitive dissonance is a necessary ingredient in changing behavior by pointing out hypocrisy, and its totally absent from Hypocrisy Theatre.

For a lot of the people foisted on stage and cast in the role of “Hypocrite,” they never experience cognitive dissonance. Here are two reasons.

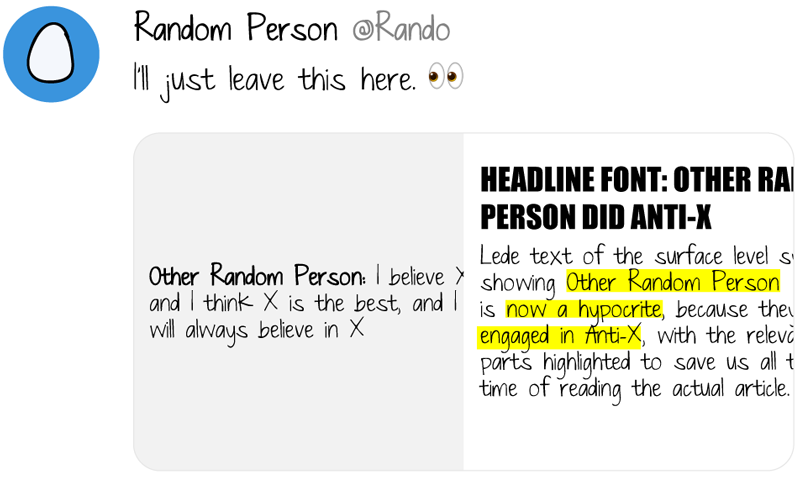

One, we’re often contrasting an X with a Y, instead of an Anti-X. They might be connected for us, but completely unrelated to “The Hypocrite.”

For example, let’s say someone said “Climate change is a problem we should all take steps to solve” (X) and later we found out they ate meat (Y). Ah-ha! Hypocrisy, thy name is you! We could call them out on that, and have them be completely dumbfounded, because they never read that article. For them, X ? Y.

Okay, but what about when we really do line up an X with a sincere Anti-X? That has to work, even in Hypocrisy Theatre, right?

Well, also no. Or, at least, often no.

Because, two, they might have a deeper value, or one that supersedes whatever we’re poking at, that rationally explains what they were doing/saying.

It’s not hypocritical if they are acting in accordance with a higher value.

And with Hypocrisy Theatre, we don’t know that, we often don’t make an effort to find that out, and we simply don’t care if someone tells us it’s true.

On the other hand, if Friend-Who-Texts-At-Dinner told us they were checking their phone because their dog was at the vet undergoing an operation, and they are awaiting updates, we’d probably give them a hypocrisy pass.

You better. Or I’ll bite you.

Then Why Do So Many Of Us Do It?

If it doesn’t work, why are so many people doing it, all the time?

And why am I constantly feeling the urge to do it, too? To put on a little showing of Hypocrisy Theatre in my Facebook feed.

- It makes us feel good, right, better, smarter, truer, morally superior — as compared to “them” (whoever isn’t us);

- We get rewarded for doing it Right with likes, and follows, and clicks, and other things that are hard to distinguish from progress or growth; and

- It obfuscates our real goal, tricking us into thinking that pointing out other people’s bad is the same as doing good.

Now, it’s at this point that I want to call your attention to something that might not have been obvious: so far, I’ve presented all of this as ideologically neutral.

That is, there isn’t a particular ideology, belief set, political faction, or mindset that participates in Hypocrisy Theatre. It’s a show for everyone, like Wicked.

Because of this, a lot of us doing simply because other people in our circles are doing it.

We’re not thinking about the overall goals of our work, life, or actions.

We’re not thinking about effecting the change we believe is possible in our hearts.

We’re not really thinking at all, besides, maybe, “What’s the harm?”

What’s the Harm?

Hypocrisy Theatre reduces complicated, multi-dimensional, intersectional, and nuanced viewpoints into two-sentence hot takes.

It motivates us to seek the approval of people who already agree with us, at the expense of everyone else. The likes. The retweets. “If you’re getting hated on, you must be doing something right.”

It tells us that it’s okay to think for someone else, to ignore their values, and to dismiss them altogether. “We don’t need them, we have us.”

It lulls us away from whatever our goals are, or figuring out the actions that could line up with our values, because it’s far more comfortable, easy, and safe to just point out what others are doing wrong, than it is to create something right. “They’re so backwards lol.”

Hypocrisy Theatre is also everywhere, all the time, playing in every town and social media profile, and it’s so easy to catch a show and the cast changes so often that it’s become hard to really care about it any more. Like Wicked.

And no one mourns the Wicked.