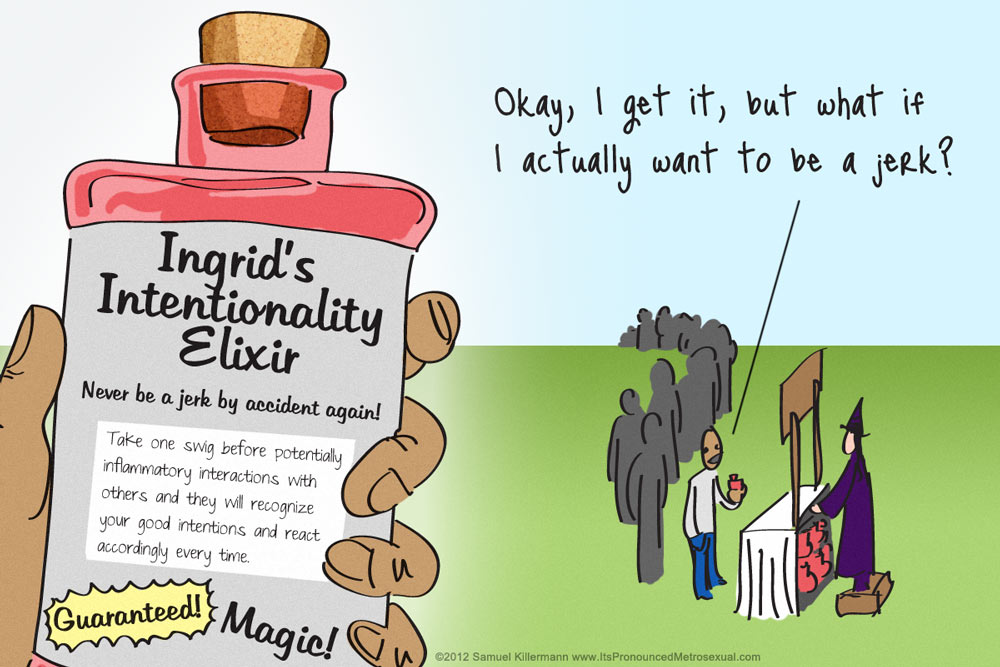

I’ve created a few graphics about when it’s okay to say “gay” and the one argument that keeps coming up goes something like “How can you regulate language? What’s offensive to one person is not to another. What matters is your intentions.”

To that, the first and most important thing I have to say is this: Your intentions don’t matter as much as the effect of your actions.

I will elaborate on my response to that question more in a bit, but first I want to pose another question, and posit an answer.

Why the fascination with intentions?

There are a couple of things at play here that lead to the focus on the intentions rather than the outcome: the ideas of “political correctness” and “victim blaming,” and, most importantly, how they interact. Before I can explain the interaction, let me explain what they are.

Victim Blaming 101

The phrase “blaming the victim,” coined by psychologist William Ryan in his mid-70s book about race and poverty, is tossed around a lot these days surrounding instances of rape (and date-rape). The concept hasn’t changed much in the past forty years. So, what is it?

Victim blaming is when a perpetrator of some crime deflects the fault back on to the person they committed the against, effectively justifying the crime and absolving themselves of any guilt. As I mentioned before, the most common time you’ll hear about this these days is in cases involving rape, and the most common argument is “she was asking for it” (usually because of how she was dressed or because of the previous relationship with the offender).

Sound screwy to you? Then you’re in the minority. Most people seem to think that rape victims are at least partially to blame for being raped. That says a lot about a lot, but tuck it away for a minute while we focus on the other part of this equation.

“Political Correctness”

I don’t think the graphics I make or anything I do here or in my live show is encouraging being “politically correct.” I support being inclusive. I wrote an entire article about the difference between being inclusive and politically correct, so I’ll let you read that if you want to hear more. For this article, all that’s important is knowing that a lot of people oppose my graphics (and my life in general) because they oppose the idea of being “PC.”

The opposition to “political correctness” appears to be strong across the political spectrum. Regardless of left or right leanings, people don’t like to be told what to say, and they don’t like being censored. I echo those feelings.

The problem is how this gets twisted into some confusing and contradictory outcomes.

Victim Blaming + Political Correctness = Intentions > Outcomes

If math isn’t your thing, the heading here means that victim blaming and political correctness interact in such a way that it leads folks to believe and support the idea that intentions are more important than outcomes. As I mentioned before, outcomes are what matter most (more on that in the next section), so this is a problem. But how does it happen?

The Situation

Let’s consider an example related to the graphic that spawned this article: knowing the “right” label to use. A well-intentioned person calls his gay friend “a homosexual,” because he’s concerned that gay is an inflammatory term (happens all the time). He is trying to be a good dude, and a good friend. But his friend corrects him, pointing out that “gay” is a better term, and “homosexual” has negative, science-experimenty, uncomfortable vibes.

The Reaction

The well-intentioned friend is now spurned, because he feels that he was trying his best to be inclusive, and his friend is just (a) nit-picking, (b) impossible to please, (c) asking too much, or (d) has a problem with straight people. He argues, either verbally with his friend or nonverbally with himself in his head, that he meant well, and his friend should recognize that.

The Problem

People, in general, don’t like to be told what to say — this goes for well-intentioned people as well as jerks. When our well-intentioned person went out of his way to say what he thought was the “right” thing, we was stretching himself in two ways: he was saying something he wasn’t comfy with, but saying it because he thought it was “PC” (i.e., “right”); and he was taking a risk to try and be a good dude to his friend at the expense of failing and feeling like a jerk. And when that happened we jumped from the Political Correctness frying pan into the Victim Blaming fire.

Being corrected by an individual when he already feels like he’s being “corrected” by society at large (being “PC”), is tough medicine to swallow. Throw in the fact that the reason he was being “PC” was due to empathetic concern for his friend’s feelings and wants — his intent was to make his friend feel safer/comfier/faster/stronger (sorry, went Daft Punk there) — and you have a recipe for emotional confusion.

To protect himself from feeling like a bad person (he’s not, mind you, but people are quick to take a correction for a particular behavior as code for “you’re a bad person”), he has to deflect blame to someone or something else. He can get pissed at society for wanting him to be “PC,” or he can get pissed at his friend for being impossible to please. This is how victim blaming works. Making this seem like his friend’s fault will make him feel better about himself — after all, his friend is the gay one, he has to expect to be misunderstood or mislabeled. He’s basically asking for it.

Why do outcomes matter more than intentions?

So here’s the real doozy. This is a fight I fight every day. Why am I fighting a war against well-intentioned folks? Well, I’m not. I think well-intentioned folks are awesome. I identify as a well-intentioned person. But I’m going to stick by my guns: intentions, in the grand scheme, don’t mean squat.

When good intentions go bad

The first (and biggest) issue I have with intentions is how often good intentions go bad. And a really common reason they go bad is because we, as individuals, have individual wants and needs that are different from one another. How you manifest your good intentions and how I manifest mine are likely different, and how the object of our intentions receives them will likely be just as different. We often treat others how we want to be treated, instead of how they want to be treated (read more on that here).

You see this pan out especially bad when there is a cultural divide. What is good or nice or helpful in one culture is not necessarily good or nice or helpful in another. In fact, it might end up being just the opposite. Intentions are flawed.

But it’s the thought that counts

Nope, actually it’s not. How can you count on another person knowing what you’re thinking, and knowing that you mean well? Even amongst close friends arguments are often caused due to the slightest bit of misunderstanding, why would you not expect this to happen with strangers?

Let’s say I bought a gift for my good friend that I thought she would absolutely love (true story). Now let’s say that this gift turned out to be something that triggered an incredibly visceral, damaging memory from her past (also true story). Should she wear this thing and tote it around because of how thoughtful I was, or should tell me what happened and decline the gift? She certainly felt pressured to do the former (because it was a gift, and beggars can’t be choosers, and it’s the thought that counts, and other cliches), but thankfully for her well-being and our friendship she did the latter (end of story).

Intentions are capricious and theoretical

In any relationship (between two individuals, a teacher and a class, between one group and another) there are going to be countless interactions, all bearing an immeasurable weight of intentions. Those intentions are bound to change from interaction to interaction and be interpreted (or misinterpreted) based on the receiver’s mood or disposition.

What’s more troublesome is that intentions are theoretical agreements that are made between the intender and the intendee, without the intendee’s awareness of the agreement or the terms. You wouldn’t mentally sell someone a car, mentally draw up all the paperwork and mentally collect the money, then, after presenting this deal to the person in real life and in past tense (i.e., it already happened), snap when they aren’t okay with the “deal” they just made, would you? No, you wouldn’t.

Outcomes are consistent and real

On an individual level, outcomes are relatively consistent and predictable. If someone says X to me, I’ll likely respond Y. Or, more refined, if someone says X to me, and I’m feeling Z, I’ll likely respond Y. For example, if someone calls me a “fag,” and I’m in a good mood, I’ll respond Socratic-ly. It doesn’t matter if they said it “to be funny,” or “because you’re wearin’ them flip-flops.”

What’s even more important is that outcomes happen externally. It doesn’t matter if you didn’t mean to hit that bunny with your car, you did. You were a well-intentioned driver and now you have a dead bunny. What are you going to do about it? You can try to adjust your driving (pay more attention, drive slower, etc.), or you can blame the bunny (shouldn’t’ve been there). In either case, it happened, regardless of your intentions, and now you get to choose how to move on.

Moving beyond good intentions

When people ask me what I do for a living, I like to respond I help good people be better people. Well-intentioned people are good people. We just have a little ways to go to be better people, and it all takes place after the outcome, not before it.

Don’t take it personally

It was not my intention to include as many cliches as possible in one article, so whoops. But seriously: if you’re a well-intentioned person and your good intentions backfire, don’t take it personally. It happens. The outcome may have been bad, but that doesn’t mean you are.

There’s a difference there. We are the sum total of our experiences, we aren’t defined by one mistake. It’s easy to think that, to fall into that trap, but as soon as you take it personally when someone doesn’t react well to your good intentions things are only going to get worse.

Learn from your mistakes

You probably think I mean that, in a follow up to the last point, you should try to avoid whatever created that outcome to not have it happen again, right? Wrong. Focus less on intentions and the other people and what happened and more on yourself. If you don’t take it personally when you screw up, and you don’t get frustrated trying to be inclusive, you’ll do a much better job at all of it.

Remember, the same action with the same intention can result in an infinite number of outcomes. The only constant is you, and how you react to the reaction, regardless of how it goes. Learn what your triggers are, learn how you can lessen them, and don’t allow yourself to continue tripping over the same roots.

Open yourself up to failure/learning

It’s funny that people harp on me about how intentions should matter more and etcetera etcetera etcetera when a majority of my time each day goes to cleaning dead bunnies off my car (metaphorical dead bunnies in email and comment form — I’m not a bunny-murderer). I’m a well-intentioned person, and everything I do professionally is a manifestation of those good intentions, but the outcomes are often bad (shining example). But I’m here to fail/learn, and I’ve learned how to fail/learn gracefully. Heck, I even ask for it, and a lot of the best stuff I’ve created here has been the result of a zig-zag of failures and learning (thanks to fantastic article comments and emails).

Realizing that you’re likely going to fail and being okay with that is what helps make failing and learning become failing/learning. The two are so blurry to me that only a little slash separates them. You’re going to screw up. Count on it. I’m going to go out on a limb and use another (another) cliche here and remind you that everybody falls down, but it’s what you do when you get back up that matters.